- Home

- David O'Meara

A Pretty Sight Page 3

A Pretty Sight Read online

Page 3

across shipping lanes to another,

the marvel of Rome raided for newer money,

while the snail

plods its slime trail

twenty-seven metres each century.

•

For those who cite The Matrix, Rocky

and the CGI’d prequels to Star Wars

as good reason to hate them,

remember the Aeneid is also a sequel.

And remember a thousand years

separate Homer and Virgil, only

two thousand more between Virgil

and us. War that follows rage, the care

of fields and horses, some details might

still ring so true that he seems

near each time we hear them.

Hungry, Virgil crosses the bridge

to Trastevere, adjusts his toga

beside a line of smart cars, catching

the whiff of dinner venting through

trattorie shutters. In a doorway,

he watches the chef bent over

a scratched counter, who steadies

then chops an onion’s soft, rotten

underside until he frees crisp layers

lambent at its core, sauté s them

in olive oil with garlic,

the sizzle and smell

so familiar the poet might forget

Maecenas isn’t waiting to debate

rhetoric or Aeneas’s fate

in the gardens up the Esquiline Hill.

•

Where does the Danube start?

Magris searches in his book.

He visits Furtwangen

with friends, finds a brook

that drains into a tributary,

the exact source

an argument for centuries, inch

by sodden inch. Near a clear spring

on a hill, they reach a dip

rinsed with rivulets,

and follow a slope to a house

where they knock

at the threshold, squint into a window.

Feet shuffle through half-empty rooms

to the door

which opens on a perturbed old woman

not interested in questions.

But since they’ve

come all this way, she listens, squints

and points to a rough ditch near

a woodshed

gushing cold water. ‘The water reaches

the gutter,’ she explains,

‘through a basin,

which is constantly full because of a tap

that no one ever succeeds

in turning off.’

•

I never tire of arriving.

At Pamukkale, the wind chucked

leaves and palm fronds as we crossed

the main square.

Barefoot, we ascended

the travertine rock, its stalactites’ drip

and slow froth of calcium

like an overpoured pint of Guinness

cooled to dollops of white-rimmed shelves.

Ruins at the top,

the once-bustling spa town of Heirapolis,

its paving stones still rutted

by the wear of cart wheels.

Here you can walk past the colonnades

of antiquity’s shops. Wealthy Romans

took the hot springs here, retired

and died, their sarcophagi

accumulating to another kind

of stop for tourists north of the baths.

Shells of modern tourism too, lobby fragments

from the 1970s, more evidence of

how eras settle, retreat,

each strata engraved as ghost structure.

This abandoned front desk, the green

marble floor at dusk, light like soft copper,

haunting as any wheel rut

crowded with weeds –

you can find them if you follow

these unmarked goat tracks

further still.

•

‘If I cannot bend the higher powers,

I will move the infernal regions.’

A favourite quote of Freud’s

and the Secessionist painters of Vienna,

lovers of the glimpse, the held-back, what

beats at your insides to claw a way out.

I wrote it down looking at Klimt’s Attersee

in the Leopold Museum south of the Ringstrasse.

The words are Juno’s in Virgil’s Aeneid,

a summation of alternative options

for those cast outside the party line.

The ode to Plan B.

Attersee might be landscape

as subversive frill,

the lake’s abstract surface

stroked with turquoise

over green and blue underpaint

like the bangled skies of Van Gogh.

Klimt’s lake

stretches, infinitely if it could,

to the top edge of canvas

and the dark, heavy shape painted there,

an island or shoreline that by limiting

the infinite has given it value.

•

I thought I saw Sophie Scholl

in a club underground

in Warsaw

that we found by following smokers

down an alley and steep, concrete stairwell,

through tobacco fog to air-sucking bass.

She was nodding at the mosh edge,

beer clutched in her hand

in that post-Cold War dance hall.

I wanted to ask how she got there –

roaming the rebuilt

squares of Mitteleuropa – but she looked

too happy to bother

with dredging up the past. Anyway, what

would be the question?

Is everything changed, or the same?

knowing any answer won’t change

the hour of closing time. In that basement’s low ceiling

and sticky floor, furnished

in the dumpster vogue

of old fridges and mismatched chairs,

Sophie hardly blinked, swigged

her drink, her silence meant

as challenge to ‘put up or shut up’

or just ‘shut up and listen.’

In the speakers’ blare

I left her there.

•

We were returning from the north,

an overnight train

from Sa Pa, sharing a sleeping berth

with two young women from Switzerland.

It was 4 a.m. as the rubbed glow

of the station platform settled in our window.

We lugged backpacks

through the puzzle of Hanoi’s Old Quarter,

amazed at its paused frenzy, dark shops

locked behind metal gates, a few motorbikes

chainsawing past. A cafe opened at 5:30

and agreed to hold our packs

so we wandered to Hoan Kiem Lake

to watch the tai chi groups

balance inner tensions at sunrise.

By then, completely transformed,

the market and streets were stacked

with baskets: crab, pork,

pineapple pyramids, oysters

and sleek trout hawked by vendors,

attendants sweeping park paths

with long, wiry brooms. Police brewed tea

in their dawn kiosk, caps

angled back

off their foreheads

near stereos wired to trees

for the tai chi grannies, conjuring

longevity with techno beats.

Hanoi’s traffic and street life,

no history but the deal, offers

and banter, the good price of fish

caught that morning

in the Gulf of Tonkin.

Fuck silence or permanence.

Fu

ck elegy. Fuck time and pain.

•

Dawn sky, sriracha red,

Chiang Mai lunch, khao soi and mango,

a stockpile of sun before

another carousel of departure level,

the sucker-punch intake of takeoff.

Past weightless snatches of sleep,

the drop

to the terminal bus, that sub-zero palanquin

aloft over road drifts

of Baltic night:

watch as we hurried through snowfall

to brew tea and read in the lamplight

of a Helsinki hostel.

•

Olduvai, really Oldupai,

named for the fronded sisal plant

that grows here. Seen from space,

the Rift’s a patchwork

in algal patina, the gorge

a grey-green collage splayed

with evaporated rill beds,

steep cracks tracking the landscape

like plate sutures on a skull. Snacking

on sandwiches, we sat under

corrugated tin, protected

from the sun’s hazy weight,

rock monolith and broken scrub

hedging the Earth’s curvature.

Three and a half million years back,

three apes, predate of humans,

walked past at Laetoli through drops

of soft rain, the shapes of their prints

left by the ash layer, cemented

in tuff, stable enough to last

as the hot and grey ash fell.

Other marks: birds, a hare,

a three-toed horse

and its foal turning

in the opposite

direction. Dimpling the site,

rainprints too. But this trio, tracks

tagged 61, 62 and 63,

we know walked upright, as a habit;

left no knuckle marks, the gait

a ‘small-town walking speed’

like a stroll through the agora.

Tempting to speculate

about the story of their travel,

a family or hunting group

looking for signs of a water hole

in the wake of the volcano’s

tremors, one set of their prints

nested in the hollow of another,

the way we can follow

someone through snow

to make the going a little easier.

•

On a charity box in the Hanoi airport:

‘For Especially Difficult Children.’

Or ‘We Beg for Silent Behaving’ outside

the Basilica of St. Euphemia

in Rovinj, Croatia.

I mention this not from smugness

but as point of argument. If language blurs

across cultures in the same decade,

how will our songs and stories

translate across ticking inches of drift?

The challenge of Onkalo,

‘hiding place,’ a toxic dump

cored through granite in Finland.

Blasters descend through rock

five kilometres deep,

bore igneous strata, each layer

another geologic age.

So when they drive

their pickups down and walk

through curtains of dust, are

they descending back through time

in corridors designed to be resealed

and forgotten for a thousand centuries?

How silent it will be, down

there, when the ventilation fans

stop whirring,

the new Ice Age crested

and gone, Earth’s surface scoured

like a child’s ribboned aggie found

in the grass near a gravel road.

We’ll have no language

to warn of what we built, no marker

left to explain the world

wiped clear of any signs of us.

‘My bones would rest much easier,’

Virgil wrote, ‘if I knew your songs

would tell my story in days to come.’

•

Let me be quieter. Go

slow and listen.

Near Lake Manyara,

the unhurried swish

of elephants

gnashing through branches

as we sat for an hour

just watching. Ibises rested

in the umbrella acacias,

velvet monkeys

in the grass. Remember

the Ngorongoro Crater?

We stood on its rim

past dusk; uninterrupted herds

of wildebeest and zebra

migrating below

the distant lightning storm.

Go slow, I thought. Listen.

That morning, as we left

Arusha, our truck passed

a group of Masai

headed to town.

‘How do they get around?’

‘They walk. They’ll walk

to Nairobi. You can’t

walk like the Masai.’

The warriors leaned

on their spears, waiting

to cross the red dirt

of the Serengeti road.

Easy to imagine

their indifferent looks

as pre-Homeric,

outwaiting time

with a cubist view,

so looking out

is always looking in,

so wherever you turn,

you arrive just

as you’re leaving,

though I knew

a likely goal in town

might be the internet,

or to change

from dyed shuka

to tailored suits

and a government posting.

•

At the check-in counter at Heathrow,

I took a snap of our backpacks.

Who knows what we really need?

Baggage for some estate lawyer

to inventory, and meanwhile we’re carried

like stowaway snails on shipped marble

through Earth’s shallow atmosphere,

that dark shape near the edge of the canvas.

•

Virgil, don’t be our guide; you wouldn’t

know the way around now.

Wandering below the Palatine

in hopes of a dinner invitation,

you’d need to pause at every turn

between fountains, churches,

papal scavenging

or Domitian’s renos further on.

The Christ thing? Long story;

born nineteen years after you died,

he changed the architecture, to put

it mildly. That’s just the start.

Since I’m buying lunch, let’s stop at one

of these pizza counters that line

the tourist route and I’ll explain

coffee, tomatoes and pasta to you.

Here’s the Pantheon, its columns and porch

propped on the sudden rotunda.

You know the site as Agrippa’s temple,

gone now, yes, but step inside,

they’ve done wonders.

Marvel at the symmetric swirl

of its ceiling tiles, the open dome

tipping light and rain across the stone.

Hey, I know a good fish place

not far from here, just down

from the Campo de’ Fiori, that serves

battered cod and antipasti

with a decent jug of vino sfuso.

Nothing fancy. A lino floor, white linen

thrown across a few rough tables; the waiters

Old World Romans who rush

to shake your hand at the exit.

It’s around here, I swear, somewhere,

though it’s been a couple of years

and you never know

how business will go, I don’t need

to tell you. All that’s fallen or torn down

evades our partial gaze

yet ruins still wait to brush against us

from the afternoons they were raised.

If you’ve asked us to wait

by this intersection, it must be the feel

of something familiar, a turn

in the street where the plastered

porticoes of insulae once stood.

You could close your eyes, cued by pigeon trills,

and hear the cart wheels on basalt,

or smell the reek of garum

before engines interrupt, and cellphones.

Contrails rib the sky.

‘In Event of Moon Disaster’

– William Safire (July 1969)

After Borman,

NASA’s liaison, calls

and urges ‘some alternative posture’

should things go south – unforeseen glitch,

miscalculation,

technical whatever – leaving

Armstrong and Aldrin

stranded on the moon,

does Safire walk or run

to the Oval Office?

The president’s aides rustle

around the furniture, their minds

touchy and tentative

like bees

in a cactus patch.

You can imagine Dick’s face

when advised: cut all

communication, commend

their souls to ‘the deepest

of the deep,’ like a burial at sea.

Then call their wives.

As for text, it’s left

to Safire

to get the spirit right. Christ,

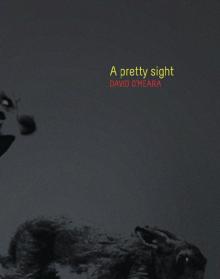

A Pretty Sight

A Pretty Sight